Marine litter is a collective term for any persistent, manufactured or processed solid material discarded, disposed of or abandoned in the marine and coastal environment. It includes a wide variety of slowly degradable items. The main sources from land include tourism, sewage, fly-tipping, local businesses and unprotected waste disposal sites. The main sea-based sources are shipping and fishing, including abandoned and lost fishing gear.

Marine litter is a persistent problem affecting the seabed, the water column and coastlines. It poses risks to a wide range of marine organisms, such as seabirds, marine mammals and turtles, through ingestion and entanglement, and has economic impacts for local authorities and on a range of sectors, for example aquaculture, tourism, power generation, farming, fishing, shipping, harbours, and search and rescue. Sixty-five percent of items monitored on beaches are plastic. These degrade very slowly over hundred-year time scales and are prone to breaking up into small particles. The widespread presence of microscopic plastic particles and their potential uptake by filter-feeding organisms is of increasing concern given the capacity of plastic particles to absorb, transport and release pollutants.

International and EU legislation addressing sources of litter includes the MARPOL Convention Annex V, and the EU Port Waste Reception Facilities Directive. In 2007, OSPAR published Guidelines for the implementation of Fishing for Litter projects in the OSPAR area.

Since 1998, OSPAR has monitored levels of beach litter, initially through a pilot project and then through a voluntary monitoring programme. Despite initiatives to reduce the amount of marine litter in the OSPAR area, overall levels in areas monitored are frequently unacceptable. Beaches in the OSPAR area have an average of 712 litter items per 100 m. Levels have remained relatively constant, but with a slight increase in input from the fishing industry. Region III and the northern part of Region II have more litter than Region IV and the southern part of Region II Figure 9.14.

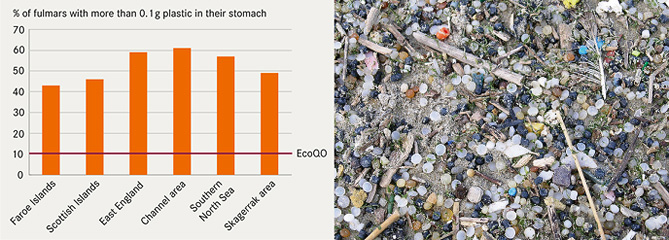

There are limited data on seabed and floating litter, but those studies that do exist show that the amounts of litter on the seabed can vary widely and that litter may accumulate in certain areas. Marine litter also finds its way to the deep sea, and is regularly observed by scientists studying the seabed with submersibles or remotely operated vehicles. An Ecological Quality Objective (EcoQO) for the North Sea on plastic particles in seabirds’ stomachs has helped to identify the extent of floating litter at sea. Associated studies have shown that 94% of birds have small pieces of plastic in their stomach and a high percentage have more than the level set for the EcoQO.

Additional efforts are needed to stop litter entering the marine environment both from sea-based and land-based sources. Efforts to address sea-based sources include environmental education for professional seafarers, methods to prevent abandoned fishing gear, cooperation on enforcement and awareness-raising, as well as FFL initiatives. For land-based sources, improved waste management, including waste reduction and recycling, will help reduce the problem. OSPAR should extend its marine litter monitoring on beaches to all Regions and consider including it in its Coordinated Environmental Monitoring Programme, taking into account the monitoring requirements of the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive. This may result in a requirement to monitor the water column and the seabed. OSPAR should support the implementation of international and EU legislation, initiatives such as UNEP’s (Regional Seas Programme) work on marine litter, and ongoing research into litter in the deep sea and the ecological effects of microplastics.